Weitere Sprachen

Weitere Optionen

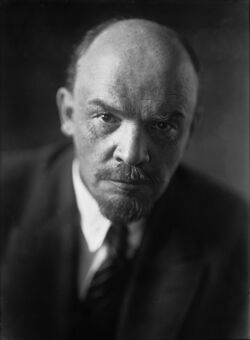

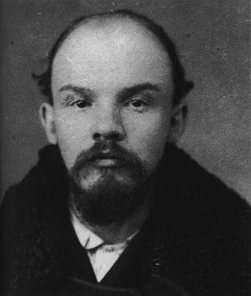

Wladimir Iljitsch Lenin Владимир Ильич Ульянов | |

|---|---|

| |

| Geboren | Wladimir Iljitsch Uljanow 22. April 1870 Simbirsk, Russisches Reich |

| Gestorben | 21. Januar 1924 (53 Jahre alt) Gorki, RSFSR, Sowjetunion |

| Todesursache | Schlaganfall |

| Nationalität | Russisch |

| Politische Überzeugung | Marxismus |

| Partei | Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Russlands |

Wladimir Iljitsch Lenin war ein russischer Revolutionär, politischer und wirtschaftlicher Theoretiker, Philosoph und Staatsmann. Er war der führende Kopf der Oktoberrevolution, die zur Gründung der Union der Sozialistischen Sowjetrepubliken führte, der ersten erfolgreichen Diktatur des Proletariats.

Lenins bedeutendster Beitrag zur marxistischen Theorie war seine Imperialismustheorie, die die Dominanz von Monopolen und Kartellen beschreibt. In zahlreichen Schriften trug er zudem wesentlich zur Entwicklung einer marxistischen Praxis bei, welche die Strategie und Taktik der Revolution, die marxistische Staatstheorie und die Strukturierung einer proletarischen Organisation durch den demokratischen Zentralismus umfasste.

Lenins politische und theoretische Aktivitäten, seine Schriften der 1890er Jahre und des frühen 20. Jahrhunderts, sein entschlossener Kampf gegen Opportunismus und revisionistische Verzerrungen der marxistischen Theorie sowie sein Engagement für die Schaffung einer revolutionären politischen Partei gelten als spezifische Beiträge Lenins zum Marxismus. Diese Beiträge werden heute als Marxismus-Leninismus bezeichnet.

Leben[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Frühe Jahre (1870–1888)[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Wladimir Iljitsch Uljanow wurde am 22. April 1870 in Simbirsk geboren und war das vierte von acht Kindern von Ilja Uljanow, einem angesehenen Pädagogen und Sohn eines ehemaligen Leibeigenen, und Maria Alexandrowna, die aus einer adligen Familie stammte.[1] Lenins Vater war zwar selbst kein Revolutionär, teilte jedoch progressive Ansichten und lehnte die autokratische Staatsform ab. Sowohl sein Vater als auch seine Mutter prägten Lenins intellektuelle Erziehung stark. Neben seinen Eltern übte auch sein Bruder Alexander großen intellektuellen Einfluss auf ihn aus, da er Lenin erstmals mit marxistischer Literatur vertraut machte.[2]

Lenins Kindheit und Jugend fielen in eine reaktionäre Phase der russischen Geschichte, in der Zivilpersonen häufig für ihre Kritik am zaristischen Regime verhaftet wurden.[3] Im Mai 1887, als Lenin 17 Jahre alt war, wurde sein Bruder Alexander Uljanow öffentlich hingerichtet, da er an einem Attentatsversuch auf Zar Alexander III. beteiligt gewesen war. Dieses Ereignis trug maßgeblich zu Lenins Radikalisierung und seinem späteren revolutionären Engagement bei.[4]

Am 13. August 1886 wurde Lenin an der juristischen Fakultät der Universität Kasan zugelassen und trat einen Monat später der Samara-Simbirsk-Bruderschaft bei, einer damals verbotenen Studentenvereinigung, was gemäß der Universitätsstatuten zur Exmatrikulation führen konnte.[3][5] Ein Jahr nach Beginn seines Studiums beteiligte sich Lenin an studentischen Kampagnen und Demonstrationen, die das Recht auf studentische Vereinigungen forderten und die Wiedereinsetzung zuvor exmatrikulierter Studenten verlangten.[3] Aufgrund seiner Teilnahme an diesen Protesten wurde Lenin im Dezember 1887 verhaftet, von der Universität verwiesen und für ein Jahr in ein nahegelegenes Dorf verbannt, wo er fortan unter strenger Polizeiaufsicht stand.[3]

Während seines Exils im Dorf Kokuschkino widmete sich Lenin intensiv dem Studium der politischen Ökonomie und anderer wissenschaftlicher Werke. Später schrieb er über diese Zeit: „Ich glaube nicht, dass ich jemals in meinem Leben so viel gelesen habe, nicht einmal während meiner Gefangenschaft in St. Petersburg oder meines Exils in Sibirien, wie in dem Jahr, als ich aus Kasan in das Dorf verbannt war; ich las gierig von frühmorgens bis spätabends.“[3]

Im Herbst 1888 wurde Lenin die Rückkehr nach Kasan gestattet, jedoch ohne die Möglichkeit, sein Studium wieder aufzunehmen oder an ausländischen Universitäten zu studieren. Zurück in Kasan schloss er sich einem von Nikolai Fedossejew organisierten marxistischen Studienkreis an und begann mit seinen ersten politischen und revolutionären Aktivitäten. In dieser Zeit, 1888–1889, studierte Lenin erstmals das erste Buch von Karl Marx „Das Kapital“.[3]

Frühe revolutionäre Aktivitäten (1889–1895)[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Im Mai 1889 zog die Familie Uljanow in ein Dorf nahe der Stadt Samara, wo Lenin nur knapp einer erneuten Verhaftung durch die Geheimpolizei entging, die kurz darauf Mitglieder der marxistischen Studienkreise von Fedossejew in Kasan verhaftete und inhaftierte. In Samara verdiente Lenin seinen Lebensunterhalt durch Nachhilfe. Da ihm der Besuch der Universität untersagt war, stellte er mehrfach Anträge, die Universitätsprüfungen ohne Vorlesungsbesuch abzulegen. 1890 erhielt er die Genehmigung, sich 18 Monate lang autodidaktisch vorzubereiten. Nach intensivem Studium legte er 1891 die Prüfungen mit Bestnoten in allen Fächern ab und erhielt ein Diplom erster Klasse.[6]

Lenin begann, als Anwalt am Regionalgericht in Samara zu arbeiten und trat 1892–93 etwa zwanzigmal als Verteidiger vor Gericht auf. Sein juristisches Engagement blieb jedoch zweitrangig, da er sich intensiv dem Studium des Marxismus widmete, um sich auf seine revolutionäre Arbeit vorzubereiten. 1892 gründete Lenin den ersten marxistischen Zirkel in Samara, der sich auf Werke von Marx, Engels und Plekhanow konzentrierte.[6] Die juristische Praxis bereicherte Lenins Verständnis der realen Welt, da er so aus der Perspektive der wirtschaftlich Benachteiligten konkrete Beispiele des Klassenkampfes und die Grenzen der bürgerlichen Rechtsordnung erlebte.[5]

1893 verfasste Lenin seine erste theoretische Arbeit unter dem Titel Neue ökonomische Entwicklungen im Leben der Bäuer*innen, eine Analyse der russischen Wirtschaft basierend auf Daten und Statistiken über die bäuerliche Landwirtschaft.[6] Während dieser Zeit korrespondierte er mit Nikolai Fedossejew und tauschte Ansichten über marxistische Theorie sowie über die wirtschaftlichen und politischen Entwicklungen Russlands aus. Lenin erinnerte sich später mit großer Wertschätzung an diese Freundschaft und schrieb: „Fedossejew spielte in der Wolgaregion und in Teilen Zentralrusslands eine sehr wichtige Rolle; die damalige Hinwendung zum Marxismus war zweifellos maßgeblich seinem außerordentlichen Talent und seiner Hingabe als Revolutionär zu verdanken.“[7]

Im August 1893 ging Lenin nach St. Petersburg, wo er an mehreren Treffen marxistischer Kreise teilnahm. Dort übte er scharfe Kritik an den liberalen Narodniki und legte so die Grundlage für sein 1894 veröffentlichtes Werk Was die ‚Freunde des Volkes‘ sind und wie sie die Sozialdemokrat*innen bekämpfen. Diese Schrift, die in drei Teilen illegal in russischen Städten verbreitet wurde, schuf das theoretische Fundament für das Programm und die Taktik der russischen revolutionären Sozialdemokratie.[8][5] In dieser Zeit lernte Lenin auch Nadeschda Krupskaja kennen, die kostenlos Arbeitende unterrichtete.[9]

Gründung einer vereinten marxistischen Organisation und Verhaftung (1895–1897)[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Im März 1895 nahm Lenin an einer Konferenz sozialdemokratischer Gruppen aus St. Petersburg, Moskau, Kiew und Wilno teil.[10] Die Konferenz diskutierte den Übergang von der marxistischen Propaganda in kleinen Zirkeln zu einer breit angelegten politischen Agitation, die Veröffentlichung populärer Literatur für die Arbeitsklasse und die Schaffung engerer Kontakte zu diesen. Man beschloss, zwei Vertretende ins Ausland zu senden, darunter Lenin.[11]

Von Mai bis September 1895 reiste Lenin ins Ausland, um im Exil lebende Sozialdemokraten zu treffen, insbesondere Plekhanow. In Berlin begegnete er erstmals Wilhelm Liebknecht, einem deutschen Sozialdemokraten, und in Paris traf er Paul Lafargue, den Schwiegersohn von Karl Marx und sozialistischen Aktivisten.[12][13][5] Anlässlich des Todes von Friedrich Engels am 05. August 1895 verfasste Lenin eine kleine Broschüre, die Engels' Beitrag zur proletarischen Sache würdigte.[14] Im selben Jahr vereinten sich die marxistischen Zirkel von St. Petersburg zu einer einzigen politischen Organisation unter Lenins Führung. Im Dezember nahm diese Organisation den Namen Bund für den Kampf zur Befreiung der Arbeitsklasse an.[11] Die Gruppe hatte bereits Monate zuvor die Arbeitenden durch Flugblätter aufgewiegelt und sich an Streiks beteiligt, was zur Verhaftung Lenins und anderer Führer des Bundes am 20. Dezember 1895 führte. Lenin wurde wegen „staatsfeindlicher Verbrechen“ angeklagt und zu vierzehn Monaten Einzelhaft sowie drei Jahren Verbannung nach Sibirien verurteilt.[11][5]

Während seiner Haftzeit setzte Lenin seine revolutionäre Arbeit fort und fand schnell Mittel und Wege, mit nicht inhaftierten Genoss*innen in Kontakt zu treten, um die Aktivitäten des Bundes zu koordinieren. In seiner Zelle schrieb er das Entwurfsprogramm für den ersten Kongress des Bundes und begann mit den Recherchen und dem Verfassen seines Buches Die Entwicklung des Kapitalismus in Russland. Um die Zensur zu umgehen, nutzte er Milch als unsichtbare Tinte, die erst durch Erwärmung oder in heißem Wasser sichtbar wurde.[11][15] Über Krupskaja, die sich als Lenins Verlobte ausgab, konnte er weiterhin mit den Mitgliedern des Bundes korrespondieren.[16]

Sibirische Verbannung (1897–1900)[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Nach über vierzehn Monaten Haft wurde Lenin zu drei Jahren Verbannung im Dorf Schuschenskoje in Ostsibirien unter polizeilicher Überwachung verurteilt. Das Urteil wurde ihm am 13. Februar 1897 verkündet.[17] In einem Brief aus dem Jahre 1897 an seine Mutter und Schwester bat Lenin um Werke von Karl Marx und Friedrich Engels in französischer Sprache, darunter Das Elend der Philosophie, Kritik der Hegelschen Rechtsphilosophie und ein Kapitel aus Anti-Dühring.[18] Nadeschda, die seit August 1896 ebenfalls inhaftiert war, erhielt im Dezember 1897 die Erlaubnis, Lenin in Schuschenskoje zu besuchen, nachdem sie sich als seine Verlobte ausgegeben hatte.[19] Im Mai 1898 traf sie im Dorf ein, und einen Monat später heirateten die beiden.[20][21]

Während seines Exils verfasste er hauptsächlich zwei Werke: Die Aufgaben der russischen Sozialdemokraten, in dem er die praktische Arbeit der russischen Sozialdemokrat*innen als die Verbreitung des wissenschaftlichen Sozialismus und den Kampf gegen den Zarismus darstellte[22], und Die Entwicklung des Kapitalismus in Russland, eine detaillierte und gründlich recherchierte Untersuchung der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung Russlands, die 1899 unter einem Pseudonym veröffentlicht wurde. Das Buch argumentierte für ein revolutionäres Bündnis zwischen Arbeitsklasse und Bäuer*innen angesichts der historischen Bedingungen des zaristischen Russlands und zeigte, dass sich unter den Bäuer*innen ein Prozess der ökonomischen Differenzierung vollzog, wobei einige zu Kulaken, der ländlichen Bourgeoisie, wurden.[23]

Im März 1898 fand in Minsk der erste Kongress der Russischen sozialdemokratischen Arbeiterpartei (RSDAP) statt, der die Partei gründete und zeigte, dass die Organisation trotz der Verhaftung ihrer Führungskräfte wuchs.[24] Trotz ihrer Mängel[25] bezeichnete Lenin die Gründung der RSDAP als „den größten Schritt, den die Russische Arbeiterbewegung in ihrer Verschmelzung mit der russischen revolutionären Bewegung gemacht hat“.[26] Mit der Veröffentlichung seines Werks "Die Entwicklung des Kapitalismus in Russland" begann Lenin seinen ideologischen Kampf gegen die Narodniki und gegen die Marxist*innen, die ausschließlich innerhalb der liberalen Gesetzesgebung handelten,[27] darunter besonders Eduard Bernstein, dessen Ideen Lenin als „einen Versuch, die Theorie des Marxismus zu verengen und die revolutionäre Arbeiterpartei in eine reformistische Partei zu verwandeln“ beschrieb.[28]

Die Idee der Schaffung einer einheitlichen marxistischen Partei in Russland stand im Mittelpunkt von Lenins Schriften während seines Exils in Sibirien. Er verfasste drei Artikel für die Arbeiter*innenzeitung, die als offizielles Organ der RSDAP angenommen worden war, darunter Unser Programm,[29] Unsere unmittelbare Aufgabe[30] und Eine dringende Frage.[31] Diese Artikel wurden erst 1925 veröffentlicht, da das Zentralkomitee verhaftet wurde und die Zeitung der RSDAP vernichtet wurde.[32] Nach dem Ende seiner Verbannung durfte Lenin nicht in Universitätsstädten oder großen Industriezentren wohnen und wählte einen Wohnsitz in der Nähe von St. Petersburg.[33]

Entwicklung einer proletarischen Partei (1900–1903)[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Nach seiner Rückkehr aus dem Exil musste Lenin Verbindungen zu den sozialdemokratischen Organisationen knüpfen. Auf dem Weg von Sibirien nach Pskow machte er zunächst in der Gouvernement Ufa Halt, um seine Ehefrau Nadeschda Krupskaja und seine Schwiegermutter zu besuchen und ihnen bei der Einrichtung ihres Lebensortes für die Dauer von Krupskajas Exil zu helfen.[34] Dort traf er auch auf andere Sozialdemokrat*innen, die in der Region im Exil lebten, und stellte ihnen seinen Plan zur Gründung einer revolutionären Zeitung vor, die die Möglichkeiten für die Aktivitäten der russischen Marxist*innen erweitern sollte.[35]

Den Großteil des Jahres 1900 verbrachte Lenin mit Reisen innerhalb Russlands und ins Ausland, um mit Sozialdemokrat*innen über die Herausgabe einer russischen marxistischen Zeitung und Zeitschrift zu beraten.[36] Während dieser Zeit verfasste er einen Entwurf für die Erklärung der Redaktion von Iskra[lower-alpha 1] und Sarja[lower-alpha 2], in dem er die Aufgabe der Gründung einer gesamtrussischen sozialdemokratischen Zeitung als den „ersten Schritt“ auf dem Weg zu einem offenen politischen Kampf beschrieb.[37]

Im Sommer 1900 diskutierte Lenin mit Georgi Plechanow über die Herausgabe der Zeitung Iskra. Plechanow forderte dabei eine privilegierte Position in der Redaktion, was zu hitzigen Auseinandersetzungen mit Lenin führte und ihre Beziehung schwer belastete.[38] Plechanows Verhalten hatte einen tiefgreifenden Einfluss auf Lenin, wie in dessen Schrift namens Wie der „Funke“ beinahe erlosch' deutlich wird.[39] Darin schildert Lenin seine Enttäuschung über Plechanows gereiztes, verwirrtes und manipulierendes Verhalten.

Trotz dieser Schwierigkeiten gelang es Lenin gegen Ende des Jahres, eine Übereinkunft mit Plechanows Gruppe Befreiung der Arbeit zu erzielen. In der von Lenin verfassten Erklärung der Redaktion von Iskra wurden die Aufgaben dargelegt, die zerstreuten sozialdemokratischen Gruppen unter dem gemeinsamen Banner des revolutionären Sozialismus zu einer starken Partei zu vereinen und eine ideologische Einheit gegen opportunistische Strömungen herzustellen. Die erste Ausgabe der Iskra enthielt einen Artikel von Lenin mit dem Titel Die dringenden Aufgaben unserer Bewegung. Darin erklärte er, dass die Hauptaufgabe der Sozialdemokrat*innen zu dieser Zeit im Sturz der Autokratie und in der Verbreitung der Ideen des wissenschaftlichen Sozialismus in die Massen bestehe.[40]

Das gesamte Jahr 1901 widmete Lenin der Redaktion und dem Verfassen von Artikeln für die Iskra.[41] Unter diesen Artikeln war auch Was tun?, in dem Lenin betonte, dass die Rolle einer Zeitung „nicht nur in der Verbreitung von Ideen, in der politischen Bildung und in der Gewinnung politischer Verbündeter besteht. Eine Zeitung ist nicht nur ein kollektiver Propagandist und Agitator, sie ist auch ein kollektiver Organisator.“ In diesem Beitrag unterstrich Lenin erneut die Notwendigkeit einer gesamtrussischen Zeitung und einer einheitlichen revolutionären sozialdemokratischen Partei.[42]

Gegen Ende des Jahres 1901 begann Wladimir Iljitsch, das Pseudonym „Lenin“ zu verwenden, ohne dass ein bestimmter Grund für die Wahl dieses Namens bekannt ist.name.[43]

In den Jahren 1901–1902 arbeitete die Redaktion der Iskra an der Ausarbeitung eines Programms für die Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Russlands (RSDAP) als Vorbereitung auf den Zweiten Parteikongress. Dabei traten scharfe ideologische Differenzen zwischen Plechanow und Lenin zutage. Beide verfassten unterschiedliche Programmentwürfe, die später von einem eigens eingesetzten Komitee zu einem einheitlichen Programm zusammengeführt wurden. Besonders hervorzuheben ist, dass Lenin auf die Aufnahme der Diktatur des Proletariats als unverzichtbare Voraussetzung für die Revolution im Parteiprogramm bestand.[44]

Im Jahr 1902 veröffentlichte Lenin sein berühmtes Werk Was tun?, in dem er eine umfassende Analyse der opportunistischen Tendenzen in den sozialdemokratischen Organisationen Europas vorlegte.[45] Zudem behandelte er in diesem Buch organisatorische Fragen und Probleme der russischen Sozialdemokratie seiner Zeit und bekräftigte die Notwendigkeit einer geeinten revolutionären sozialdemokratischen Partei.party.[46]

Der Programmentwurf für die Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Russlands (RSDAP) wurde im Juni 1902 in der Iskra veröffentlicht. Auf dem Zweiten Parteikongress der RSDAP, der von Juli bis August 1903 stattfand, wurde das Programm mit geringfügigen Änderungen angenommen. Dieses Programm blieb bis nach der Revolution im Jahr 1919 das offizielle Parteiprogramm.[47]

Die Tagesordnung des Zweiten Parteikongresses umfasste die Diskussion des Parteiprogramms, Fragen der Parteiorganisation sowie die Wahl des Zentralkomitees und der Redaktion des zentralen Parteiorgans. Lenin führte auf diesem Kongress einen entschlossenen Kampf gegen die weiterhin bestehenden opportunistischen Strömungen der sogenannten „Ökonomisten“ auf der Grundlage ideologischer und organisatorischer Prinzipien.[48]

Als Ergebnis des Kongresses erhielten Lenins Anhänger die Mehrheit der Stimmen in den Parteiwahlen und wurden fortan als Bolschewiki[lower-alpha 3] bekannt, während die oppositionelle Minderheit als Menschewiki[lower-alpha 4] bezeichnet wurde.

Verweise[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- ↑ Tamás Krausz (2015). Reconstructing Lenin: an intellectual biography: 'Family'. ISBN 9781583674499 [LG]

- ↑ “Lenin war auch stark von seinem älteren Bruder Alexander beeinflusst, der für ihn eine unbestrittene Autorität darstellte. Der junge Wladimir orientierte sich an seinem Bruder, und wann immer er eine Entscheidung treffen sollte, antwortete er: „Ich würde tun, was Alexander tun würde.“ Dieses Bestreben, sein Verhalten nach dem seines älteren Bruders zu richten, verlor sich nicht, sondern vertiefte sich mit der Zeit und gewann an Bedeutung. Von Alexander erfuhr Wladimir erstmals von marxistischer Literatur, und es war in den Händen seines Bruders, dass er zum ersten Mal Das Kapital von Karl Marx sah.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Childhood and youth. The beginning of revolutionary activity; The shaping of revolutionary views' (p. 15). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ 3,0 3,1 3,2 3,3 3,4 3,5 Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Childhood and youth. The beginning of revolutionary activity; The shaping of revolutionary views'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ Robert Service (2000). A biography of Lenin: 'Deaths in the family'. ISBN 9780333726259 [LG]

- ↑ 5,0 5,1 5,2 5,3 5,4 Tamás Krausz (2015). Reconstructing Lenin: an intellectual biography: 'Who was Lenin?; Education'. ISBN 9781583674499 [LG]

- ↑ 6,0 6,1 6,2 Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Childhood and youth. The beginning of revolutionary activity; The Samara period'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ Vladimir Lenin (1922). A few words about N. Y. Fedoseyev. [MIA]

- ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Leader of the revolutionary proletariat of Russia; The ideological defeat of Narodism'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Leader of the revolutionary proletariat of Russia; Among the St. Petersburg Proletariat'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ “2 or 3 March: Lenin takes part in a meeting of members of social democratic groups from St Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev and Vilno. Passing from propaganda work in Marxist circles to mass agitation work is debated.”

Gerda Weber & Hermann Weber (1974). Lenin: life and works: '1895' (p. 7). [LG] - ↑ 11,0 11,1 11,2 11,3 Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Leader of the revolutionary proletariat of Russia; The League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ “15 May-8 June: Lenin travels to Switzerland; he meets Potresov in Geneva and travels with him to see Plekhanov who is on holiday in the mountain village of Les Ormonts, near Les Diablerets. [...]

Before 8 June: Lenin travels to Paris and gets to know Paul Lafargue, Karl Marx's son-in-law, there. [...]

14 September: In a letter to Wilhelm Liebknecht, Plekhanov recommends Lenin as 'one of our best Russian friends' and requests that Lenin be received because of an 'important matter' as he is returning to Russia. Lenin visits Wilhelm Liebknecht in Charlottenburg between 14-19 September.”

Gerda Weber & Hermann Weber (1974). Lenin: life and works: '1895' (pp. 7-9). [LG] - ↑ “In Europe in 1895, he met the elders of Russian Marxism: Plekhanov and Axelrod in Switzerland, Paul Lafargue (Marx’s son-in-law) in Paris and Wilhelm Liebknecht in Berlin.”

Tariq Ali (2017). The dilemmas of Lenin: 'Terrorism and utopia; The younger brother' (pp. 44-45). [LG] - ↑ Vladimir Lenin (1895). Friedrich Engels. [MIA]

- ↑ “Sie kamen jeden Samstag mit Milch geschrieben – dem Tag, an dem Bücher verteilt wurden. Ein kurzer Blick auf das geheime Zeichen zeigte, dass das Buch eine Botschaft enthielt. Um sechs Uhr wurde heißes Wasser für Tee verteilt, und die Aufseherin führte die unpolitischen Strafgefangenen zur Kirche. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt hatte man den Brief bereits in Streifen geschnitten und den Tee zubereitet. Sobald die Aufseherin den Raum verließ, begann man, die Papierstreifen in den heißen Tee zu tauchen, um den Text sichtbar zu machen.”

Nadezhda Krupskaya (1933). Reminiscences of Lenin: 'St. Petersburg'. [MIA] - ↑ “So-and-so had no one coming to visit him – it was necessary to get him a "fiancee": or so-and-so had to be told through visiting relatives to look for letters in such-and-such a book in the prison library, on such-and-such a page; another needed warm boots, and so on.”

Nadezhda Krupskaya (1933). Reminiscences of Lenin: 'St. Petersburg'. [MIA] - ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile' (p. 51). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ “I should like to have Saint-Simon and also the following books in French:

K. Marx. Misère de la philosophie. 1896. Paris.

Fr. Engels. La force et l’ économic dans le développement social.

K. Marx. Critique de la philosophie du droit de Hegel. 1895.

all these are from the “bibliothèque socialiste internationale” where Labriola came from.

All the best,

V. U.”

Vladimir Lenin (1897). December 21, 1897 letter to his mother and sister. [MIA] - ↑ “I was banished to the Ufa Gubernia for three years, but obtained a transfer to the village of Shushenskoye in the Minusinsk Uyezd, where Vladimir Ilyich lived, by describing myself as his fiancee.”

Nadezhda Krupskaya (1933). Reminiscences of Lenin: 'St. Petersburg'. [MIA] - ↑ “Krupskaya arrived in Shushenskoye early in May 1898 together with her mother Yelizaveta Vasilyevna. Lenin and Krupskaya were married on July 10. They set up house together, started a small kitchen garden, planted flowers and hops in the yard. The young couple lived in peace and harmony.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; In Shushenskoye' (p. 54). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “The name of his love, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya—who was arrested in the same case as Vladimir Ilyich albeit much later, on 12 August 1896—came up often in his letters. In his letters from 19 October, 10 December, and 21 December 1896 (from Shusha to Moscow, addressed to his mother, Manya, and Anyuta), he wrote to his relatives that Nadezhda Konstantinovna might join him soon, for she had received permission to choose Shushenskoye instead of northern Russia”

Tamás Krausz (2015). Reconstructing Lenin: an intellectual biography: 'Who was Lenin?; The personality of Lenin as a young man in exile and as an émigré'. ISBN 9781583674499 [LG] - ↑ “The object of the practical activities of the Social-Democrats is, as is well known, to lead the class struggle of the proletariat and to organize that struggle in both its manifestations: socialist [...], and democratic [...]

The socialist activities of Russian Social-Democrats consist in spreading by propaganda the teachings of scientific socialism, in spreading among the workers a proper understanding of the present social and economic system, its basis and its development, an understanding of the various classes in Russian society, of their interrelations, of the struggle between these classes, of the role of the working class in this struggle, of its attitude to wards the declining and the developing classes, towards the past and the future of capitalism, an understanding of the historical task of international Social-Democracy and of the Russian working class. [...]

Let us now deal with the democratic tasks and with the democratic work of the Social-Democrats. Let us repeat, once again, that this work is inseparably connected with socialist activity. [...] Simultaneously with the dissemination of scientific socialism, Russian Social-Democrats set themselves the task of propagating democratic ideas among the working class masses; they strive to spread an understanding of absolutism in all its manifestations, of its class content, of the necessity to overthrow it, of the impossibility of waging a successful struggle for the workers’ cause without achieving political liberty and the democratization of Russia’s political and social system.”

Vladimir Lenin (1898). The tasks of the Russian social-democrats. [MIA] - ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; The development of capitalism in Russia'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; In Shushenskoye' (p. 54). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ “The First Congress of the R.S.D.L.P. was attended by only nine persons. Lenin was not present because at that time he was living in exile in Siberia. The Central Committee of the Party elected at the congress was very soon arrested. The Manifesto published in the name of the congress was in many respects unsatisfactory. It evaded the question of the conquest of political power by the proletariat, it made no mention of the hegemony of the proletariat, and said nothing about the allies of the proletariat in its struggle against tsardom and the bourgeoisie.”

Vilhelm Knorin, Pyotr Pospelov & Yemelyan Yaroslavsky (1938). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The struggle for the creation of a social-democratic labour party in Russia (1883–1901); Lenin's struggle against Narodism and "legal Marxism." Lenin's idea of an alliance of the working class and the peasantry. First congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party'. [MIA] - ↑ Vladimir Lenin (1899). A retrograde trend in Russian social-democracy. [MIA]

- ↑ Vilhelm Knorin, Pyotr Pospelov & Yemelyan Yaroslavsky (1938). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The struggle for the creation of a social-democratic labour party in Russia (1883–1901); Lenin's struggle against Narodism and "legal Marxism." Lenin's idea of an alliance of the working class and the peasantry. First congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party'. [MIA]

- ↑ “The notorious Bernsteinism—in the sense in which it is commonly understood by the general public, and by the authors of the Credo in particular—is an attempt to narrow the theory of Marxism, to convert the revolutionary workers’ party into a reformist party. As was to be expected, this attempt has been strongly condemned by the majority of the German Social-Democrats. Opportunist trends have repeatedly manifested themselves in the ranks of German Social-Democracy, and on every occasion they have been repudiated by the Party, which loyally guards the principles of revolutionary international Social-Democracy. We are convinced that every attempt to transplant opportunist views to Russia will encounter equally determined resistance on the part of the overwhelming majority of Russian Social-Democrats.”

Vladimir Lenin (1899). A protest by Russian social-democrats. [MIA] - ↑ “It made clear the real task of a revolutionary socialist party: not to draw up plans for refashioning society, not to preach to the capitalists and their hangers-on about improving the lot of the workers, not to hatch conspiracies, but to organize the class struggle of the proletariat and to lead this struggle, the ultimate aim of which is the conquest of political power by the proletariat and the organization of a socialist society.”

Vladimir Lenin (1899). Our programme. [MIA] - ↑ “It is the task of the Social-Democrats, by organizing the workers, by conducting propaganda and agitation among them, to turn their spontaneous struggle against their oppressors into the struggle of the whole class, into the struggle of a definite political party for definite political and socialist ideals. This is some thing that cannot be achieved by local activity alone.”

Vladimir Lenin (1899). Our immediate task. [MIA] - ↑ “The main objection that may be raised is that the achievement of this purpose first requires the development of local group activity. We consider this fairly widespread opinion to be fallacious. We can and must immediately set about founding the Party organ—and, it follows, the Party itself—and putting them on a sound footing. The conditions essential to such a step already exist: local Party work is being carried on and obviously has struck deep roots; for the destructive police attacks that are growing more frequent lead to only short interruptions; fresh forces rapidly replace those that have fallen in battle. The Party has resources for publishing and literary forces, not only abroad, but in Russia as well. The question, therefore, is whether the work that is already being conducted should be continued in “amateur” fashion or whether it should be organised into the work of one party and in such a way that it is reflected in its entirety in one common organ.”

Vladimir Lenin (1899). An urgent question. [MIA] - ↑ “While in exile Lenin gave much thought to the plan of founding a Marxist party. He expounded it in his articles "Our Programme", "Our Immediate Task" and "An Urgent Question" written for Rabochaya Gazeta (Workers' Gazette) . In the autumn of 1 899, Lenin accepted an offer to be the editor of this newspaper and then to contribute to it. The paper was recognised by the First Congress of the R.S.D.L.P. as the official organ of the Party, but the police closed it shortly after. In 1899, an attempt was made to resume publication. But the attempt failed and Lenin's articles remained unpublished. They first saw light of day in 1925.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; The plan for a Marxist party' (pp. 65-66). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “At the end of his exile Lenin’s thoughts were occupied with the problem of putting into effect his plan for creating a revolutionary- proletarian party. Lenin looked forward eagerly to the day when his term of exile would be over, fearing that the tsarist authorities, as often happened, might prolong his term. He became nervous, slept poorly and lost weight. He longed to be doing active work.

Luckily, Lenin’s apprehensions proved groundless – his term was not prolonged. Early in January 1900, the Police Department sent Lenin a notice to the effect that the Minister of the Interior had forbidden him to reside in the capital and university cities and large industrial centres after the completion of his term of exile. Lenin chose Pskov as his place of domicile to be nearer to St. Petersburg.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; The plan for a Marxist party' (pp. 67-68). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “Only one thing shadowed the joy of complete freedom for revolutionary activity: the necessity of separation from his wife, who had still a year to spend in exile in Ufa Gubernia. How would she live this year, in what conditions? On the way back from Siberia Lenin stopped off in Ufa with his wife and mother-in-law and helped them to get settled.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type' (p. 69). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “On his first day in Ufa Lenin met with A. Tsyurupa, V. Krokh mal and A. Svidersky, Social-Democrats living in exile in that city, and acquainted them with his plan for setting up a revolutionary newspaper which opened up broad possibilities for the activities of the Russian Marxists.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; Preparations for founding an all-Russia newspaper' (p. 69). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ Marxists Internet Archive (2003). The life and work of V.I. Lenin: '1900'. [MIA]

- ↑ “Russian Social-Democracy is already finding itself constricted in the underground conditions in which the various groups and isolated study circles carry on their work. It is time to come out on the road of open advocacy of socialism, on the road of open political struggle. The establishment of an all-Russian organ of Social-Democracy must be the first step on this road.”

Vladimir Lenin (1900). Draft of a Declaration of the Editorial Board of Iskra and Zarya. [MIA] - ↑ “Plekhanov, like the other members of his group, approved the idea of such Marxist periodicals. But he considered himself entitled to a privileged position on the editorial board, and his arrogance was such as to exclude the possibility of normal collective work. Lenin, who stood always for collective effort, could not accept this stand. The programme of the newspaper and magazine and the problems of publication and of joint editorial work were discussed at conferences held in Belrive and Corsier (near Geneva). The disagreement with Plekhanov came out with particular force during the conference at Corsier, attended by Lenin, Plekhanov, Zasulich, Axelrod and Potresov. The discussion here was very heated, and relations were strained almost to the breaking point.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; Preparations for founding an all-Russia newspaper' (p. 69). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “There was also “friction” over questions concerning the tactics of the magazine, Plekhanov throughout displaying complete intolerance, an inability or an unwillingness to understand other people’s arguments, and, to employ the correct term, insincerity. We declared that we must make every possible allowance for Struve, that we ourselves bore some guilt for his development, since we, including Plekhanov, had failed to protest when protest was necessary (1895, 1897). Plekhanov absolutely refused to admit even the slightest guilt, employing transparently worthless arguments by which he dodged the issue without clarifying it. This diplomacy in the course of comradely conversations between future co-editors was extremely unpleasant.”

Vladimir Lenin (1900). How the "Spark" was nearly extinguished. [MIA] - ↑ “The entire history of Russian socialism has led to the condition in which the most urgent task is the struggle against the autocratic government and the achievement of political liberty. Our socialist movement concentrated itself, so to speak, upon the struggle against the autocracy. On the other hand, history has shown that the isolation of socialist thought from the vanguard of the working classes is greater in Russia than in other countries, and that if this state of affairs continues, the revolutionary movement in Russia is doomed to impotence. From this condition emerges the task which the Russian Social-Democracy is called upon to fulfill — to imbue the masses of the proletariat with the ideas of socialism and political consciousness, and to organize a revolutionary party inseparably connected with the spontaneous working-class movement. Russian Social-Democracy has done much in this direction, but much more still remains to be done.”

Vladimir Lenin (1900). The urgent tasks of our movement. [MIA] - ↑ Marxists Internet Archive (2003). The life and work of V.I. Lenin: '1901'. [MIA]

- ↑ Vladimir Lenin (1900). Where to begin?. [MIA]

- ↑ “It was at the end of 1901 that Vladimir Ilyich began to use the pseudonym "Lenin" in some of his writings. People often ask what lay behind the choice of name. Pure chance, most probably, as was the case with the other names, Lenin's associates would reply.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; The spark will kindle a flame' (p. 78). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “In January 1902, Lenin presented critical remarks on Plekhanov's draft. He strongly criticised, also, the second draft that Plekhanov submitted. The ideas presented; Lehin pointed out, were formulated far too abstractly, particularly in the parts dealing with Russian capitalism. Further, the second draft omitted "reference to the dictatorship of the proletariat"; it failed to stress the leading role of the working class as the only truly revolutionary class ; it spoke, not of the class struggle of the proletariat, but of the common struggle of all the toiling and exploited; it did not sufficiently bring out the proletarian nature of the Party.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; The spark will kindle a flame' (pp. 79-80). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “Disclosing the international nature of opportunism, Lenin showed that, while assuming different forms in different countries, in its content opportunism remained everywhere the same. In France it found expression in Millerandism; in England, in trade-unionism; in Germany, in Bernsteinism; in Russian Social-Democracy, in Economism.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; What is to be done?' (p. 83). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “A considerable part of What is to be done? was devoted to organizational questions, on which, too, Lenin gave battle to the Economists. Restricting the concept of the political tasks of the proletariat, the Economists belittled the leading role of the party in the working-class movement, depreciated its organizational tasks. They justified the amateurish methods, petty practicality, and lack of unity of the local organizations. Lenin once more comprehensively substantiated the necessity for building up a centralised, united organization of revolutionaries. To achieve that, he pointed out, it was necessary that every attempt to depreciate the political tasks and restrict the scope of organizational work be denounced by the mass of the party's practical workers.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; What is to be done?' (p. 86). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “The draft programme of the R.S.D.L.P. drawn up by the Editorial Board of Iskra and Zarya was published in Iskra, No. 21, June 1, 1902, and the Second Congress of the R.S.D.L.P., held July 17-August 10 (July 30-August 23), 1903, adopted the Iskra draft programme of the Party, with minor changes.

The programme of the R.S.D.L.P. existed until 1919, when a new programme was adopted at the Eighth Congress of the R.C.P. (B.). The theoretical part of the programme of the R.S.D.L.P., which described the general laws and tendencies of capitalist development, was included in the new programme of the R.C.P.(B.), on V. I. Lenin’s proposal.”

Marxists Internet Archive (2003). Material for the preparation of the programme of the R.S.D.L.P. [MIA] - ↑ “The Congress agenda included twenty items, the most important of these being: the Party Programme; the organisation of the Party (adoption of the Party Rules); and election of the Central Committee and of the editorial board of the Central Organ.

[...]

Lenin, and with him the firm Iskrists, fought at the Congress for the building of the Party on the basis of ideological and organizational principles advocated by Iskra, for a solid and militant party, closely bound up with the mass working-class movement – a party of a new type, differing fundamentally from the reformist parties of the Second International. Lenin and the Iskrists sought to found a party that would be the vanguard, class-conscious, organized detachment of the working class, armed with revolutionary theory, with a knowledge of the laws of development of society and of the class struggle, with the experience gained in the revolutionary movement.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; At the Second Congress of the R.S.D.L.P' (pp. 94-95). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]